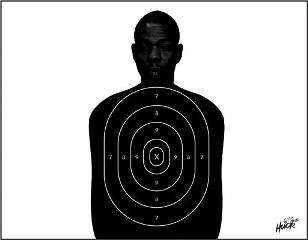

In the past two years white America has been forced to acknowledge what black people have known all their lives. That it is the police, not the courts, who dispense most of the “justice” in our urban centers. Whether it is Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Freddie Gray in Baltimore, or Eric Garner in New York, over and over again we see the police making the decisions that mean life or death for black men.

As an African-American man who grew up in the same Baltimore neighborhood as Freddie Gray, I wish I could say that I’m shocked, but I’m not. Every video I watch is consistent with the way the police have behaved in my community my whole life. In contrast, my white colleagues seem genuinely heartbroken by these videos and ask me how it could happen and, more importantly, why it keeps happening? I tell them the answer is simple: The system is not meant to protect people like me. It’s meant to protect people like you from people like me.

In 1967 President Lyndon Johnson called for The Kerner Report in an effort to confront the horrid racial violence that was consuming the country. Even after almost fifty years, it’s as timely a document as you are likely to find for our current racial problems. The report is prescient in its understanding of a multifaceted crisis rooted in a long system of oppression, a system that is perpetuated by poor schools, lack of job opportunities, and an abusive police culture. Here is one of its more insightful lines: “To some Negroes police have come to symbolize white power, white racism and white repression. And the fact is that many police do reflect and express these white attitudes. The atmosphere of hostility and cynicism is reinforced by a widespread belief among Negroes in the existence of police brutality and in a "double standard" of justice and protection--one for Negroes and one for whites.”

One needs to only look at the number of officers exonerated for the unwarranted killing of black men to see that this double standard is still pervasive.

In fact, reading the report today is a disturbing reminder of how little has changed, and I was faced with the uncomfortable realization that our current system is not merely the vestiges of Jim Crow, it is Jim Crow. While it has been modernized for the 21st Century, it still pushes blacks and whites apart and enforces a doctrine of separate and unequal.

The Kerner report also set out guidelines for reforming the nation’s police, calling for the elimination of “abrasive practices,” increasing community outreach, and recruiting more black officers into the force. This last point remains particularly relevant today, where, nationally, white officers outnumber their minority constituencies by 30 percentage points in the communities they serve. In many urban areas such as St. Louis and Cleveland the number is 70 percentage points or more. Just as it did fifty years ago, the divergence sets the tone for an “us versus them” mentality—infusing both cultures with distrust for one another.

While more integration and communication is needed, the killing of five police officers in Dallas and three in Baton Rouge may result in the opposite, just as race riots did in the 1960s, with police deciding to “get tough on crime,” acquiring more sophisticated weapons, and increasing their surveillance of citizens, all of which will only set back race relations further.

Then how do we move forward? White people say they just want peace. But your peace is my continued oppression. I want change. I want the police to come into my neighborhood without their God complex. Without the preconceived notion that all of us are up to no good. I want officers to make the same assumptions about me and my broken tail light that they make when they pull over a white person. And I don’t want to have to teach my son how to protect himself from the people who are supposed to protect him. That will require new attitudes and new political will. It will require experiments—changes to schools, to prisons, to the courts. And it will require massive financial backing from the government and, most likely, more taxes. If “created equal” is going to be more than a platitude, then every American should be willing to pay—with their wallet and their effort—to bring us together. It will not only make the country stronger, it’s the right thing to do.

Almost fifty years ago, we had an historic opportunity to fix this very problem. We knew what to do then, but we never did it. Now is the time.